Cuisine

It’s more than a meal. It’s a communion.

Our culinary program is moving into a series on world cuisines — French, Italian, Mexican, German, Asian, etc. The idea is to apply the techniques we’ve learned to date to specific applications based on the culinary traditions of different regions.

This is where the science meets the art. Where we use the techniques to paint a picture. So it’s worth breaking that down a bit.

What makes one country’s cuisine different from another? How do those culinary traditions form? And why do we still adhere to them today?

Cuisine is created through necessity. Hundreds of years ago, you cooked based on what was around you… what vegetables grew in your area, or what animals were domesticated/hunted in your area. The further back you go, the smaller that area was, and the greater the differences between those areas.

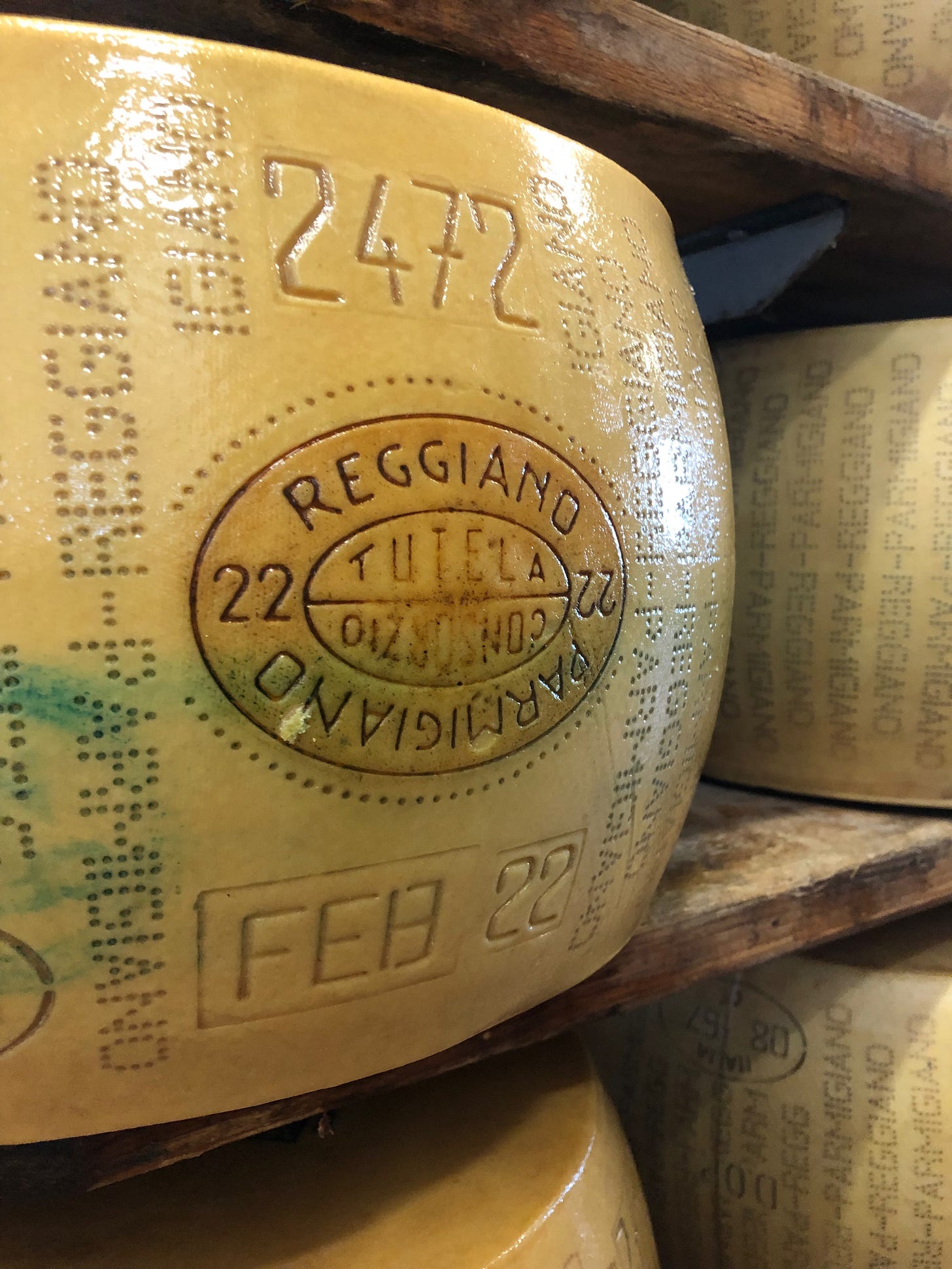

Today we think of cuisines in terms of countries, but that’s not accurate. Every country has microclimates that create subtle differences in how the same ingredients taste or are used. Even when a country shares a common language, different regions have their own unique dialect. The same goes with food.

For instance, The taste of a pig raised and cured in the mountains will be different from a pig raised and cured near the sea. What they eat, and the temperature or humidity of how they’re stored, affects their taste.

How you used those ingredients depended on the season, and how/when those ingredients were harvested. Ingredients harvested at the same time were naturally cooked together, and therefore “go” together well (“what grows together, goes together” is the saying).

That’s a bit hard to wrap your head around in today’s era of mass food distribution, when you can buy an eggplant in January. I know that until I started gardening I had no idea what produce was in season at any time. But it’s helpful to understand these regional differences when you’re cooking (or ordering) food.

So to me a country’s cuisine is more than just a restaurant “concept.” It’s more than a fad or a food trend (hello “cacio e pepe” variations). Cuisine is memory. It’s history. It’s language. Cooking or eating a dish made from traditional ingredients in the traditional style, using recipes and techniques passed down from generations, is more than simply a meal.

It’s a communion. You’re communicating with your ancestors. You’re tasting something they tasted hundreds of years ago. It’s a shared experience across generations. It’s a time machine, not unlike the passing down of folk songs, or holiday traditions.

For those of you who don’t come from a strong culinary culture, that might be hard to understand. To many people, regional cuisines simply represent different flavors, or restaurant decor. It’s just variety. And that’s OK.

But for others, eating your family’s cuisine is experiencing something more than just filling your belly or being entertained. For those of that culture, it's a constant reminder of who you are and where you come from.

And if you’re a guest at that meal, or a visitor in that restaurant, you’re being welcomed into that history. You’re getting a glimpse of another world, another perspective. It’s a chance to read a story that’s not yours and maybe, just maybe, understand something you didn’t before that meal occurred.

That’s why I say that cuisine is communication. When someone makes and shares dishes from their cuisine, they’re inviting you to know something about themselves. And speaking from the perspective of the cook, that’s often done often with a mix of both pride and vulnerability… I’m proud of my culinary heritage, but anxious about whether I did the best job of communicating it through my cooking.

We live in an interesting age where access is easy, but connection is scarce. It’s easy to find information, yet increasingly difficult to truly understand.

But eating a meal is easy. You don’t have to travel long distances, or learn a new language. You just need to eat (or cook) a meal from a region, and you’ve established a connection. You’ve gone back in time. You've traveled continents. You’ve learned languages. You’ve started a conversation. And you’ve opened the door to understanding.