Fabrication

A nice way of saying "carving up a carcass" ... and why it matters.

Many years ago I was in a grocery store meat section and saw a woman with a child of about five years old selecting ground beef. The kid was in the child’s seat of the shopping cart and doing what kids do… reaching for this, asking for that, lots of “Mommy.”

But suddenly, things took a turn.

“Mommy, there’s blood in the package!” the kid said with terror as the mom selected a pound of ground beef, wrapped in clear plastic on a styrofoam container. “They put BLOOD in the packages!”

Things pretty much disintegrated from there, with the kid going full meltdown with what I can only imagine was a conviction that we were trapped in some kind of medieval house of horrors disguised as a supermarket where leather masked men in dark back rooms injected blood into packages of what was meant to be food.

I’d bet money that kid remains a vegetarian to this day.

Yes Jimmy… meat comes from animals. Animals that are raised, slaughtered, and butchered into neat little packages for mommy to take home and make those cheeseburgers you love so much.

As adults, we’re of course aware of this. But on a certain level most of us remain not too far off from little Jimmy there in the store, with little thought for exactly where that cut of meat we just put into our shopping basket actually came from. I don’t just mean what ranch or farm. I mean what part of the animal we’re actually eating, where it came from on the body of the cow/pig/chicken, and how it got from walking around the pasture one day to laying on my plate as a slab of overcooked protein.

I was thinking about this and little Jimmy the other night in class when we walked in to see an entire hog laying on cutting boards, complete with a range of knives, what looked like a saber, and what were definitely three or so hacksaws.

Welcome to Meat Fabrication.

Fabrication is the chef term for cutting large cuts of meat into menu-sized portions. It’s the third step in that process of pasture to plate. Someone already slaughtered the animal, and someone else already butchered it. That whole chicken you see at the supermarket? That’s a butchered chicken. That sleeve of chicken thighs? That’s a chicken that’s been fabricated.

Rarely does a chef actually “dispatch” an animal themselves (the culinary term for killing something). Live lobster and fish are the only exceptions I know of.

Most of us buy whole chickens when we plan on roasting a whole chicken. We don’t carve it up until after it’s been cooked. Chefs buy whole chickens to not only roast whole, but to fabricate (or “break down”) that chicken into parts — breasts and legs — and use the leftover carcass for stock.

I’ve started exclusively buying and fabricating whole chickens for many reasons. First, practice. Second, freshness… a freshly fabricated chicken just tastes better than a bunch of parts sitting in their own fetid juices for God knows how long. Third safety… the more steps of industrial processing your meat has gone through, the higher the chance of contamination. (The riskiest meat you can buy is ground meat. A Consumer Reports investigation found salmonella in a third of the ground chicken packets it tested.)

It’s also cheaper. On a pound-for-pound basis, you’re paying far less for two breasts and two legs from a whole chicken than you are for an equal weight of chicken parts. And, you’re getting proper cuts. Bone-in chicken breasts from the store are worthless hack jobs with the ribcage still attached that makes it impossible to sear that side without removing it (which if you’re going to do, you may as well just fabricate a whole chicken to begin with).

Now hogs… nobody other than a professional chef is likely buying a whole hog and laying it out on the kitchen floor to break into pieces. But getting in there and learning how the different parts of the pig work together is fascinating.

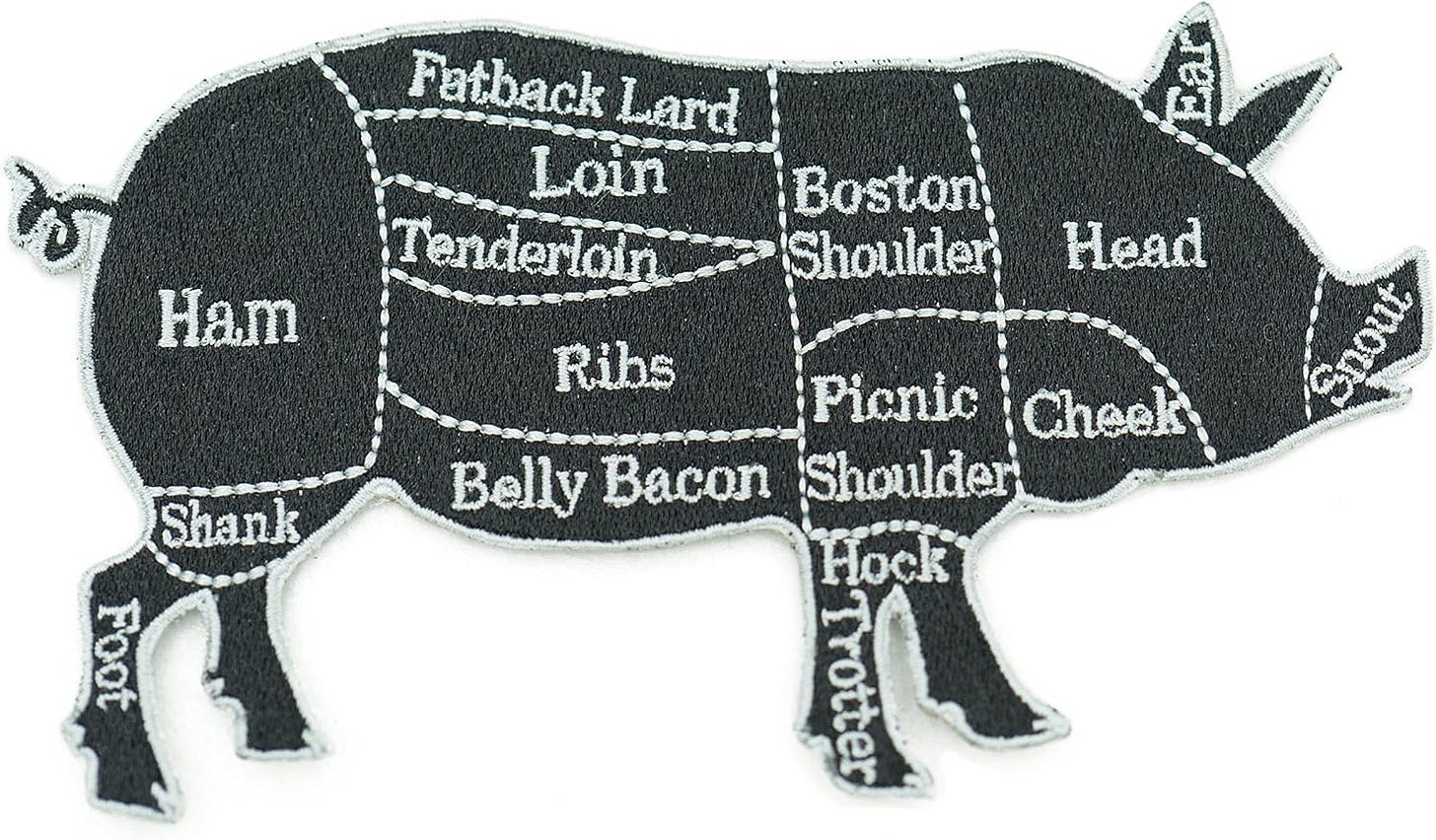

Maybe you’ve seen one of those charts outlining the different cuts of a cow or a pig a la:

But until you’re actually in there, carefully separating the loin from the ribs, and struggling with the joint where the leg meets the hip, or slicing pork chops rib-by-rib, you don’t really know.

It may sound gross, cutting away at a carcass like that. But once you get in there and start separating the different cuts, you actually forget it’s an animal and it becomes more like a puzzle. You can actually see the color difference between the cuts of meat, the line of fat, muscle, and bone between the different cuts. And most importantly… how and why each cut has a different culinary use (both eating and cooking).

For instance, you’ll forever learn the difference between spareribs and back ribs: spare ribs are the portion of the larger ribs towards the front of the animal left over (“spared”) after cutting away the bone-in pork chops (chops are the sliced section of the loin, which you can also buy whole without the bone). Back ribs are the smaller ribs towards the back of the animal, which are smaller and have less meat.

When we say “cuts” what we mean are what’s called “primals” and “sub-primals.” Primals are the main section of the animal, like for instance the chicken leg. That leg is composed of two sub-primals… the thigh and the drumstick. When you’re fabricating a chicken, you can very quickly and easily see the difference between the leg and the breasts not just based on their location, but their color and texture as well. You can see (and better understand) the difference between “white meat” and “dark meat.”

There’s also “secondary” cuts, like feet, tongue, ears, etc. And of course everyone’s favorite… offal (the liver, organs, and other stuff).

If you want to experience this with a hog or a cow… take a class. But anyone can easily buy and fabricate a chicken at home with just a quick trip to the grocery store. I highly recommend doing at least once. And maybe you’ll become like me and it’ll become a near-weekly habit (just like baking your own bread or making your own pasta).

I could write out a lot of words telling you how to fabricate a chicken. But instead I’ll just post the video of how I learned in class.

Step 1:

Remove the wing and “french” the drummette:

Sept 2:

Remove the wishbone. (Astonishingly, I didn’t actually know where the wishbone was located until this class.)

Step 3 +4

Pop open the leg bones and flatten the chicken

Score the keel bone and remove the breasts

Step 5

Remove the legs, being careful to retain the “oyster.”

Then just trim the fat/skin from the leftover carcass and retain it for Stock.

Have fun!